Federating the Social Web

Prospectus

Decentralized online social networks (DOSNs) represent a new way of organizing online communities and present both challenges and opportunities. The decentralized design of spaces like the Fediverse provide more indepdence, but this increased autonomy comes at the expense of collective action problems which must be solved in new ways. This work considers how the collective actions problems are addressed in practice and designs potential new ways to solve them.

Introduction

The social web has fundamentally changed how people connect, share information, and form communities. Like all social communities, the Web must deal with social challenges such as integrating newcomers, enforcing norms, and coordinating collective action (Kraut, Resnick, and Kiesler 2011).

Corporate platforms’ values and approaches follow the interests of their key stakeholders (Pinch and Bijker 1984); however, these approaches cannot satisfy all groups. Recommendation systems inherently must uprank some posts at the expense of others. Content moderation has inherent trade-offs which make it difficult to satisfy all possible parties. The limitations of corporate platforms have spurred people to produce alternates, including decentralized online social networks (DOSNs) like the Fediverse—–a collection of websites that pass messages between themselves using shared, open protocols.

In the Fediverse, control is distributed among various independent server operators. While this distributed design allows for more autonomy and independence, it also creates new coordination challenges and operational nuances: in a distributed system, location matters. The kind of content which is viewable and easily seen is different on each server based on their position within the network. Content moderation approaches vary from server to server. While some Fediverse software like Mastodon allows people to move accounts, attracting and retaining newcomers can be more challenging because many newcomers may lack a mental model for why they might want to join one server rather than other.

Taken as a complete body of work, this dissertation considers how federation affects the function of the Social Web. It frames the challenges of the Federated Social Web as social coordination problems. Across the studies, I use a mixed methods approach starting first with an analysis-motivated design for server recommendations, an interview study with Fediverse administrators and moderators, and a quantitative study on the effects of de-federation events (server-to-server blocks).

Background

The World Wide Web has reshaped our communication landscape with pervasive economic and cultural effects (Litan and Rivlin 2001; Crandall, Lehr, and Litan 2007; Najarzadeh, Rahimzadeh, and Reed 2014; P. DiMaggio et al. 2001). The Internet, which forms the technological underpinning for the Web, solved the problem of connecting disparate networks, computers, and operators around the world by creating a flexible system based around interoperability: protocols like TCP/IP and HTTP allowed enough standardization for meaningful communication while allowing individual systems to still experiment and retain control over their data, access, and code. One key to its success is that the largely decentralized nature of the TCP/IP protocol allowed new nodes to join the network with limited friction (Campbell-Kelly and Garcia-Swartz 2013, 28).

This approach has facilitated a strong network of person-to-person communication, developing various systems to facilitate communication between their stakeholders. Early Internet developers used email to coordinate their efforts (Leiner et al. 2009, 24, 25). Later, early online communities developed on Bulletin Board Systems, USENET, and discussion forums (Rafaeli 1984; Hauben and Hauben 1997). The blogosphere of the 2000s became a significant media power in its own right and many alumni from this era successfully transitioned into roles in traditional mass media, which itself adopted many of the norms and practices from the bloggers (Drezner and Farrell 2008). Further, the rise of social networking sites brought online communication to a larger audience (see Figure 1) and marked a shift in the organization of communities from being around topics to being around people (boyd and Ellison 2007, 219).

The history of the design and use of these systems each reflect the needs and values of the people who built and use them. Early email, for instance, was closed off to academics and government employees who quite literally met in person to plan the early email programs (Partridge 2008). As operators could easily be mapped to their real name and identities, there was less need for security and privacy protections when the protocols were first developed.

Online communities have not come without problems; connecting so much together creates a number of benefits, but it also comes with challenges. Significant resources are spent by the companies who run them to try to keep them free from spam, harassment, and illegal content (Gillespie 2018). Differences in international law and norms can make this a challenge and norms can vary by culture and location (Kaye 2019). The largest platforms have becoming increasingly closed off and less transparent to researchers (Freelon 2018). Concerns persist over the dominant economic model for the commercialized Web, which relies heavily on advertising and attention (Davenport and Beck 2001).

While the commercial Web has received significant media and lawmaker focus, it does not represent the totality of Web. Much of the early online communities were run by hobbyists and non-profit organizations (Driscoll 2022). Projects like IndieWeb have sought to create a more decentralized Web, where people own their own data and can interact with others on their own terms (Jamieson, Yamashita, and McEwen 2022). Today’s Fediverse is an extension of the original spirit of the Web: powered by the ActivityPub standard, the Fediverse is a collection of interoperable and interconnected websites that retain their independence and autonomy. With millions of active accounts, the Fediverse has established itself as a viable alternative to the commercial Web.

While significant work has gone into technical interoperability on the Fediverse (e.g. how do we pass messages between servers?), work on social interoperability is still emerging (e.g. how do we determine which servers we want to get messages from?). Fediverse servers must handle many of the challenges faced by the commercial Web in addition to some of the new challenges imposed by their decentralized design. This prospectus outlines a research agenda to understand how the Fediverse handles these challenges.

The Emergence of the Fediverse

Interoperability

A system supports interoperability when information can be exchanged between parts of the system. Interoperability can have tremendous benefits because it guarantees parts of the system can work together while at the same time supporting components that are developed or operated independently. For example, the Internet is a highly interoperable system because it allows computers and networks to communicate with each other using shared protocols. Similarly, Email allows servers and accounts to pass messages to each other using shared protocols, but run their own software of choice1.

What makes federated systems different from simple linking in practice is how they handle data. Individual nodes in a federated system do not simply link to data from other nodes in practice, but often store and replicate a copy of the data. In practice, this means such systems are less vulnerable to censorship, but it also introduces new complications regarding privacy. Deleting data from such a system is non-trivial.

Early Examples of Federated Social Websites

The Fediverse’s cultural roots are in the free software movement, which emphasizes permissive licensing and open source software. Early Fediverse projects largely attempted to create libre alternatives to corporate social media platforms (Mansoux and Abbing 2020, 125). For example, the GNU Social project (formerly known as StatusNet) was created as a free software approach to microblogging. Similarly, the Diaspora project launched in 2010, inspired by its founders’ shared concerns over the consolidation of information on the cloud (Nussbaum 2010). The network claimed over two hundred thousand users by November 2011 (Bielenberg et al. 2012) and was designed to be decentralized, with data stored and managed on independent servers known as “pods”.

More recently, the IndieWeb created a method for interlinking websites using shared standards such as Microformats 2 to mark semantic data (Jamieson, Yamashita, and McEwen 2022). Culturally, the IndieWeb often encouraged people post on their own websites and then syndicate to other websites using a system called POSSE (Post on your Own Site, Syndicate Elsewhere). Protocols like WebMentions allow IndieWeb sites to interact with each other.

ActivityPub

The ActivityPub (AP) protocol’s story starts from a place of fragmentation. While projects like GNU Social and StatusNet had a small but dedicated following, it was difficult to pass messages between servers with incompatible protocols like OStatus and Pump.io (Göndör and Küpper 2017). The ActivityPub project sought to bridge the collective of early Fediverse projects under a unifying standard and was recommended by the World Wide Web Consortium in 2018.

Although the protocols underlying the internet remains invisible for most of its users, a tremendous amount of time and effort go into their development. The development of a protocol can be challenging because it is impossible to anticipate all possible use-cases and there are trade-offs to most design decisions. ActivityPub, for instance, has been criticized for its lack of optimization and vulnerability to accidental distributed-denial-of-service attacks (Das 2024). It is important to remember that the ActivityPub standard represents the specific needs of their stakeholders at the time it was designed and adopted: namely, bridging the prior Fediverse protocols under a single, unified standard.

Fragmentation remains a challenge for DOSNs. It is hard to balance keeping wide compatibility with the creation of new and innovative features. While ActivityPub has been largely successful at bridging the fledgling communities it was designed for, further development on DOSNs may well leave AP behind. For instance, Bluesky has opted to produce its own protocol instead of adopting AP citing issues with data portability and scalability (“AT Protocol FAQ” n.d.).

Mastodon

Mastodon represents the most important Fediverse project to date. But despite its millions of registered users and coverage in major media publications, the project had humble beginnings. Eugen Rochko released the first public edition of Mastodon in October 2016. In a comment on the Hacker News thread on launch, Rochko wrote about the project’s ethos: “This isn’t a startup, it’s an open-source project. Most likely the Twitters and Facebooks will win, but people should have a viable choice… Plus this is an incredibly fun project to be working on, to be quite honest” (Rochko 2016). The software soon found an audience and eclipsed the user base of other Fediverse software.

Early reporting on Mastodon often described it an alternative to other platforms like Twitter, a framing which Zulli, Liu, and Gehl (2020) criticized.

Most Mastodon servers are small. The vast majority of Mastodon servers have fewer than 10 accounts. Many of these have only a single account. The distribution of accounts on servers, however, is highly skewed: the median server has 3 accounts, while the mean has 595 accounts.

Challenges for Online Communities

Collective Action Problems

Kollock (1998, 183) defines social dilemmas as situations where individually rational behavior leaves the collective worse off. These social dilemmas have a deficient equilibrium where there is an outcome that leaves everyone better off, but no individual incentive to move toward that outcome (Kollock 1998, 185).

Collective action problems are social dilemmas that occur when self-interested individuals have no incentive to work toward a public good (Olson 1965, 2). Hardin (1968) described one such collective action problem, where people individually overexploit shared resources, as the tragedy of the commons in a Malthusian argument against population growth. More recent scholarship, however, has shown that the tragedy of the commons is not an inevitable outcome from shared resources (Ostrom 1990). Instead, people can and do work together to manage shared resources.

Kollock (1999) argues that online communities produce public goods, often in the form of knowledge with a nearly limitless potential audience. Access to free and accurate information leaves everyone better off. This idea has been the foundation of knowledge production projects like Wikipedia and open source software projects like the Linux kernel, both of which function as public goods (non-excludable and non-rivalrous).

Due to the differences in the means of production within the Fediverse, many of the challenges faced by commercial websites are trasformed into collective action problems. These can create challenegs for the sytem as a whole. For instance, several major Fediverse servers have shut down over the years due to hosting costs. The vast majority of people with accounts on the Fediverse do not directly financially contribute to their servers—though many do.

Content Moderation

All websites which rely on third-party, user-generated content must perform some form of content moderation to remain viable (Gillespie 2018). Without it, online spaces would become dominated by spam, pornography, or other unwanted content (Gillespie 2020, 330–31). Much of this work remains largely invisible by design (Roberts 2019, 14).

While all social websites must perform content moderation, approaches vary. Large, well-resourced websites like Facebook hire teams of contractors which do the bulk of cleaning up their website. Other websites built around named subcommunities like Reddit hand off moderation duties to unpaid volunteer community members.

The small size of the average Mastodon server affects content moderation. Despite the small size of most Mastodon servers, the average Mastodon account is on a large server. Raman et al. (2019) found the top 5% of Mastodon servers host 90.6% of Mastodon accounts and send 94.8% of the posts. This means while the bulk of the moderation work concentrates on a few large servers, vulnerabilities and problems can come from a large set of smaller, less resourced servers.

Nicholson, Keegan, and Fiesler (2023) characterized the written rules on a number of Mastodon servers.

Discovery

Recommender systems help people filter information to find resources relevant to some need (Ricci, Roḳaḥ, and Shapira 2022). The development of these systems as an area of formal study harkens back to information retrieval (e.g. Salton and McGill (1987)) and foundational works imagining the role of computing in human decision-making (e.g. Bush (1945)). Early work on these systems produced more effective ways of filtering and sorting documents in searches such as the probabilistic models that motivated the creation of the okapi (BM25) relevance function (Robertson and Zaragoza 2009). Many contemporary recommendation systems use collaborative filtering, a technique which produces new recommendations for items based on the preferences of a collection of similar users (Koren, Rendle, and Bell 2022).

Collaborative filtering systems build on top of a user-item-rating (\(U-I-r\)) model where there is a set of users who each provide ratings for a set of items. The system then uses the ratings from other users to predict the ratings of a user for an item they have not yet rated and uses these predictions to create a ordered list of the best recommendations for the user’s needs (Ekstrand, Riedl, and Konstan 2011, 86–87). Collaborative filtering recommender systems typically produce better results as the number of users and items in the system increases; however, they must also deal with the “cold start” problem, where limited data makes recommendations unviable (Lam et al. 2008). The cold start problem has three possible facets: boostrapping new communities, dealing with new items, and handling new users (Schafer et al. 2007, 311–12). In each case, limited data on the entity makes it impossible to find similar entities without some way of building a profile. Further, uncorrected collaborative filtering techniques often also produce a bias where more broadly popular items receive more recommendations than more obscure but possibly more relevant items (Zhu et al. 2021). Research on collaborative filtering has also shown that the quality of recommendations can be improved by using a combination of user-based and item-based collaborative filtering (Sarwar et al. 2001).

Although all forms of collaborative filtering use some combination of users and items, there are two main approaches to collaborative filtering: memory-based and model-based. Memory-based approaches use the entire user-item matrix to make recommendations, while model-based approaches use a reduced form of the matrix to make recommendations. This is particularly useful because the matrix of items and users tends to be extremely sparse, e.g. in a movie recommendor system, most people have not seen most of the movies in the database. Singular value decomposition (SVD) is one such dimension reduction technique which transforms a \(m \times n\) matrix \(M\) into the form \(M = U \Sigma V^{T}\) (Paterek 2007). SVD is particularly useful for recommendation systems because it can be used to find the latent factors which underlie the user-item matrix and use these factors to make recommendations.

While researchers in the recommendation system space often focus on ways to design the system to produce good results mathematically, human-computer interaction researchers also consider various human factors which contribute to the overall system. Crucially, McNee et al. argued “being accurate is not enough”: user-centric evaluations, which consider multiple aspects of the user experience, are necessary to evaluate the full system. HCI researchers have also contributed pioneering recommender systems in practice. For example, GroupLens researchers Resnick et al. (1994) created a collaborative filtering systems for Usenet and later produced advancements toward system evaluation and explaination of movie recommendations (Herlocker et al. 2004; Herlocker, Konstan, and Riedl 2000). Cosley et al. (2007) created a system to match people with tasks on Wikipedia to encourage more editing. This prior work shows that recommender systems can be used to help users find relevant information in a variety of contexts.

Mastodon and other decentralized online social networks are particularily vulnerable to discovery problems. As information and accounts are spread out across many different servers, location matters in a way that is not relevant on centralized social networks. At the same time, any recommendation system run on a particular server is limited to the information on that server unless some system is in place to spread recommendations across servers, e.g. using federated machine learning.

Studies

De-federation

This study has been peer-reviewed and published as:

Colglazier, Carl, Nathan TeBlunthuis, and Aaron Shaw. 2024. “The Effects of Group Sanctions on Participation and Toxicity: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from the Fediverse”. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 18 (1):315-28. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v18i1.31316.

Content moderation in response to toxic and anti-social behavior is pervasive in social media. In general, moderation interventions strive to balance the value of wide and active user bases with the threats posed by conflicts and hate speech (Gillespie 2018). Websites that host user-generated content and sub-communities apply many kinds of policies and interventions. However, when norms diverge across interconnected, independent communities in the absence of a single (corporate or not) parent or owner, governance and moderation pose acute challenges.

A growing empirical literature has investigated social media content moderation and governance. Moderation actions most frequently target individual posts and accounts, but other group-level sanctions affect entire communities or websites. For example, Reddit has banned subreddits and Discord has blocked servers, reducing the prevalence of unwanted behavior within and sometimes beyond the targeted groups (Chandrasekharan et al. 2017, 2022; Ribeiro et al. 2021; Ribeiro et al. 2023; Russo et al. 2023; Zhang and Zhu 2011). Most prior work on group-level sanctions focuses on sanctions applied by central actors such as commercial social media platform staff. However, autonomous community administrators can also enact group-level sanctions such as when a sub-community restricts contributions from members of another sub-community. These decentralized group-level sanctions are distinct in that the targeted sub-community remains part of the larger network. To our knowledge, the effects of such sanctions remain unexplored empirically.

To investigate the effects of decentralized group-level sanctions, we analyze defederation events in the Fediverse, a decentralized social media system which consists of independently managed servers that host individual accounts and pass messages using shared protocols. Communication between servers can happen only when the administrators of both servers permit it. Server administrators can revoke such permission by “defederating” from (blocking all interactions with) specific servers. Defederation is one of the few tools administrators in a decentralized system have to protect against bad actors or enforce norms from beyond their own servers. While many defederation events on the Fediverse occur between servers with no known interaction history, many also come in response to norm violations and toxic interactions across server boundaries with a history of previous interactions. Defederations that cutoff cross-server interactions provide an opportunity to identify the effects of these group sanctions on accounts most likely to be directly affected.

We collect data from 214 defederation events between January 1, 2021 to August 31, 2022 that involved 275 servers and 661 accounts which had previously communicated across subsequently defederated inter-server connections. Using a combination of non-parametric and parametric methods, we estimate the effects of defederation on two outcomes: posting activity and toxic posting behavior among affected accounts. We find an asymmetric impact on posting activity: Accounts on blocked servers reduce their activity, but not accounts on blocking servers. By contrast, we find that defederation has no effects on post toxicity on either the blocked or blocking servers.

These findings suggest that defederation, although a common group-level sanction on the Fediverse, has mixed effectiveness: Despite the risks of severing communication channels, communities implementing group-level sanctions do not lose activity. This implies that defederation may avoid some of the costs associated with other moderation techniques such as account requirements or group sanctions like geographic blocks (Hill and Shaw 2021; Zhang and Zhu 2011). Although defederation reduces activity by blocked accounts, we did not find evidence that it made their posts less toxic. This suggests that defederation may not improve adherence to broadly held norms. Our study contributes to knowledge of content moderation on social media in that it (1) describes defederation, a novel form of group-level sanction as instantiated on the Fediverse, (2) derives hypotheses regarding the effects of defederation from prior literature, (3) creates a novel dataset of defederation events, (4) conducts a quasi-experimental analyses to quantify effects of defederation on parties affected on the blocked and blocking servers and (5) finds that defederation has asymmetric effects on activity and no measurable effect on toxicity.

Research Questions

- S1 RQ1: How does defederation impact the activity levels for affected accounts on (a) the defederated instance (blocked server); and (b) the defederating instance (blocking server)?

- S1 RQ2: How does defederation impact toxic posting behavior among the affected accounts on either (a) the blocked or (b) blocking servers?

Data

We pursue an observational, quasi-experimental research design to identify effects of defederation on the activity and toxic posting behavior in the Fediverse. We collected longitudinal trace data from 7,445 publicly listed defederation events and about 104 million public posts that occurred in the Fediverse on either the Mastodon or Pleroma networks between April 2, 2021 and May 31, 2022. Using this data, we analyze activity of user accounts (for RQ1) and the toxicity of their messages (for RQ2) on the blocking and blocked servers impacted by these events in comparison to matched control accounts. We apply a difference-in-differences approach and present both non-parametric and parametric estimates of the effects of defederation.

Methods

We used one-to-one matching, selecting the closest match according to Mahalanobis distance and discarded accounts for which there was not a sufficiently good match. Figure 5 shows the distribution of variables in the treatment and control groups, while Figure 6 shows the effectiveness of the matching process for the selection variables.

For both activity and toxicity, we present the median counts per account by week as well as the results of the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test and a difference-in-differences estimate.

Findings

| Group | median | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| $U_0$ | -135.5 | 41197.5 | 0.000 |

| $C_0$ | -18.0 | 35762.0 | 0.143 |

| $U_1$ | -54.5 | 12413.0 | 0.122 |

| $C_1$ | -53.5 | 12520.0 | 0.091 |

| $\Delta_0$ | -39.0 | 39927.0 | 0.000 |

| $\Delta_1$ | 3.0 | 10645.5 | 0.421 |

| Blocked | Blocking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term | Estimate | Std. err. | Low | High | Estimate | Std. err. | Low | High |

| \(\beta_0\) (Intercept) | 3.216 | 0.086 | 3.049 | 3.380 | 2.901 | 0.118 | 2.684 | 3.121 |

| \(\beta_1\) Group | -0.024 | 0.116 | -0.255 | 0.198 | 0.023 | 0.177 | -0.290 | 0.367 |

| \(\beta_2\) Treatment | -0.089 | 0.045 | -0.178 | 0.002 | -0.080 | 0.060 | -0.201 | 0.034 |

| \(\beta_3\) Time | 0.006 | 0.004 | -0.002 | 0.015 | -0.002 | 0.006 | -0.014 | 0.009 |

| \(\beta_4\) Treatment : Time | -0.026 | 0.006 | -0.038 | -0.014 | -0.027 | 0.008 | -0.042 | -0.010 |

| \(\beta_5\) Group : Treatment | -0.241 | 0.065 | -0.367 | -0.116 | -0.084 | 0.082 | -0.247 | 0.072 |

| \(\beta_6\) Group : Time | -0.007 | 0.006 | -0.020 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.008 | -0.010 | 0.021 |

| \(\beta_7\) Group : Treatment : Time | -0.015 | 0.009 | -0.031 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.011 | -0.013 | 0.032 |

| Group | median | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(U_0\) | -0.006 | 17746 | 0.538 |

| \(C_0\) | 0.004 | 14000 | 0.950 |

| \(U_1\) | -0.008 | 6514 | 0.619 |

| \(C_1\) | 0.001 | 5546 | 0.873 |

| \(\Delta_0\) | -0.005 | 17161 | 0.072 |

| \(\Delta_1\) | 0.000 | 6414 | 0.305 |

| Blocked | Blocking | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Term | Estimate | Std. err. | Low | High | Estimate | Std. err. | Low | High | |

| Treatment | \(\beta_0\) (Intercept) | -0.143 | 0.438 | -1.197 | 0.763 | -0.042 | 0.284 | -0.754 | 0.518 | |

| Treatment | \(\beta_1\) Treatment | 0.002 | 0.006 | -0.009 | 0.018 | -0.001 | 0.010 | -0.020 | 0.017 | |

| Treatment | \(\beta_2\) Time | 0.001 | 0.001 | -0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | -0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Treatment | \(\beta_3\) Treatment : Time | -0.002 | 0.001 | -0.004 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.002 | -0.004 | 0.003 | |

| Control | \(\beta_4\) (Intercept) | 0.136 | 0.436 | -0.907 | 1.044 | 0.048 | 0.283 | -0.613 | 0.649 | |

| Control | \(\beta_5\) Treatment | -0.000 | 0.006 | -0.016 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.009 | -0.014 | 0.024 | |

| Control | \(\beta_6\) Time | 0.001 | 0.001 | -0.000 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | |

| Control | \(\beta_7\) Treatment : Time | -0.005 | 0.001 | -0.007 | -0.003 | -0.006 | 0.002 | -0.009 | -0.002 | |

We find that the effects of defederation are asymmetric: accounts on the blocked servers decreased their posting activity (Figure 7, Table 1, Table 2) while accounts on the blocking servers did not decrease their posting activity compared to the matched controls (Figure 8, Table 3, Table 4). We found no evidence for a change in toxicity for accounts on either the blocked or blocking servers.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the effects of defederation events on the activity levels and toxic posting behavior of accounts in the Fediverse. The results indicate that such events produce asymmetric effects on activity for affected accounts on blocked servers versus those on blocking servers with no increase in toxicity for any groups. The results also highlight the potential of decentralized social networks and their unique mechanisms, such as defederation, in providing communities with tools to manage content moderation and other aspects of online interactions. Future research could explore the causes or reasons behind defederation events, the long-term consequences of defederation, as well as the mechanisms by which defederation produces (asymmetric) effects. By continuing to study the Fediverse and its affordances, we can better understand how to foster healthy online communities and effective content moderation strategies in a decentralized environment.

Newcomers and Server Recommendations

An earlier version of this study was presented at the 1st International Workshop on Decentralizing the Web and the 10th International Conference on Computational Social Science.

Colglazier, Carl. “Do Servers Matter on Mastodon? Data-driven Design for Decentralized Social Media.” 1st International Workshop on Decentralizing the Web, Buffalo, 2024.

Colglazier, Carl. “Do Servers Matter on Mastodon? Data-driven Design for Decentralized Social Media.” 10th International Conference on Computational Social Science, Philadelphia, 2024.

Following Twitter’s 2022 acquisition, Mastodon saw an increase in activity and attention as a potential Twitter alternative (He et al. 2023; La Cava, Aiello, and Tagarelli 2023). While millions of people set up new accounts and significantly increased the size of the network, many newcomers found the process confusing. Many accounts did not remain active.

Unlike centralized social media platforms, Mastodon is a network of independent servers with their own rules and norms (Nicholson, Keegan, and Fiesler 2023). While each server can communicate with each other using the shared ActivityPub protocols and accounts can move between Mastodon servers, the local experience can vary widely from server to server.

Although attracting and retaining newcomers is a key challenge for online communities (Kraut, Resnick, and Kiesler 2011, 182), Mastodon’s onboarding process has not always been straightforward. Variation among servers can also present a challenge for newcomers who may not even be aware of the specific rules, norms, or general topics of interest on the server they are joining (Diaz 2022). Various guides and resources for people trying to join Mastodon offered mixed advice on choosing a server. Some downplayed the importance of server choice and suggested that the most important thing is to simply join any server and work from there (Krasnoff 2022; Silberling 2023); others created tools and guides to help people find potential servers of interest by size and location (Rousseau 2017; King 2024).

Mastodon’s decentralized design has long been in tension with the disproportionate popularity of a small set of large, general-topic servers within the system (Raman et al. 2019, 220). Analysing the activity of new accounts that join the network, we find that users who sign up on such servers are less likely to remain active after 91 days. We also find that many users who move accounts tend to gravitate toward smaller, more niche servers over time, suggesting that established users may also find additional utility from such servers.

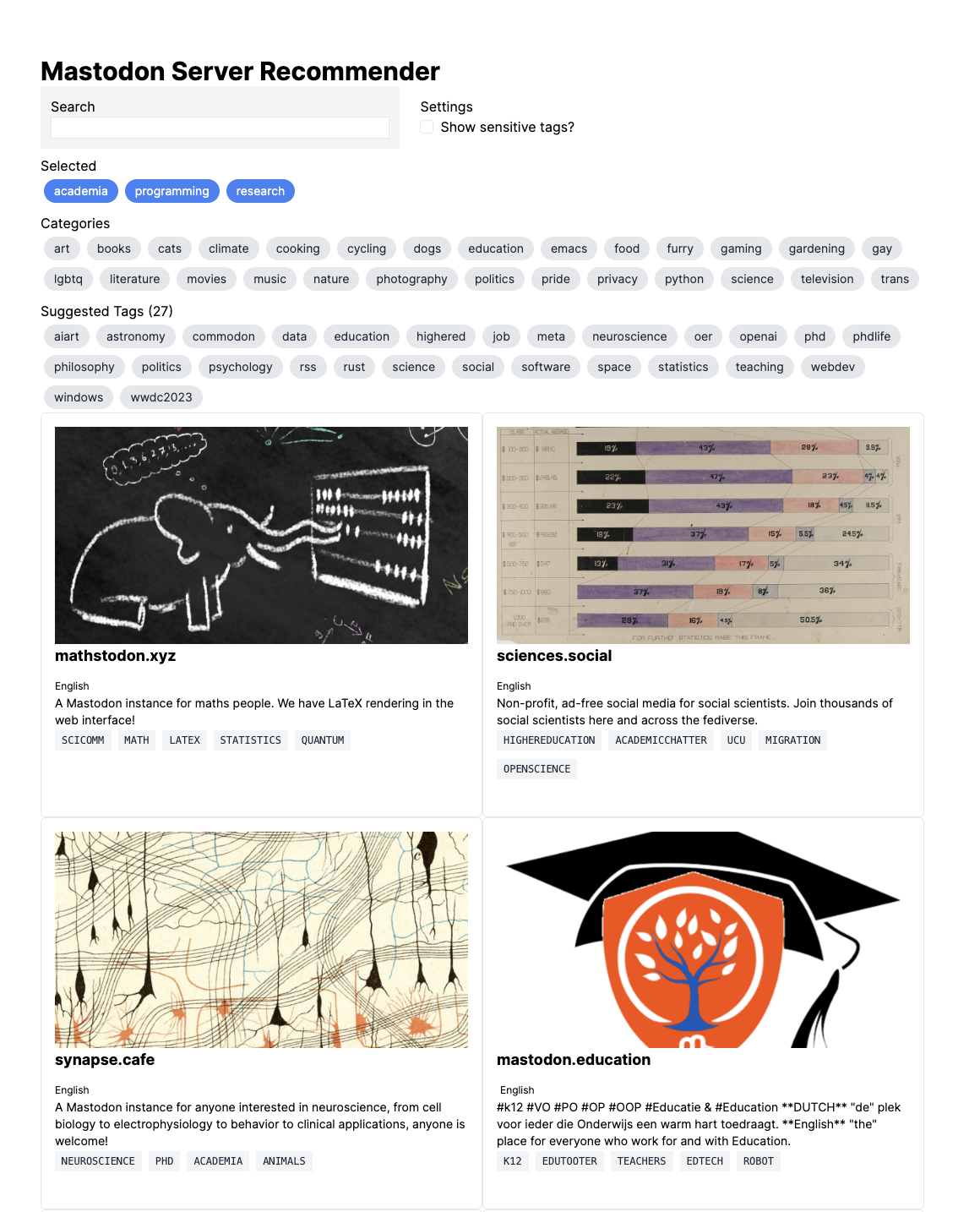

In response to these findings, we propose a potential way to create server and tag recommendations on Mastodon. This recommendation system could both help newcomers find servers that match their interests and help established accounts discover “neighborhoods” of related servers to enable further discovery.

Research Questions

- S2 RQ1: What kinds of Mastodon servers do a better job of retaining newcomers?

- S2 RQ2: How can we build an opt-in, low-resource recommendation system for finding Fediverse servers?

Data

Mastodon has an extensive API which allows for the collection of public posts and account information. We collected data from the public timelines of Mastodon servers using the Mastodon API with a crawler that runs once per day. We also collected account information from the opt-in public profile directories on these servers.

Initial Findings

Account Survival

Our initial findings suggest that servers do matter for newcomers on Mastodon. Figure 10 uses a Kaplan–Meier estimator to show that accounts on the largest Mastodon servers featured on the Join Mastodon website are less likely to remain active compared to accounts on smaller servesr featured on Join Mastodon. Further, Table 5 uses a Cox Proportional Hazard Model with mixed effects to suggest that small servers are significantly better at retaining new accounts and that general servers are less likely to retain new accounts; being featured on the Join Mastodon website appears to have no significant effect.

| Term | Estimate | Low | High | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Join Mastodon | 0.115 | 0.972 | 1.296 | 0.117 |

| General Servers | 0.385 | 1.071 | 2.015 | 0.017 |

| Small Server | -0.245 | 0.664 | 0.922 | 0.003 |

Moved Accounts

| Model A | Model B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std.Error | Coef. | Std.Error | |

| (Sum) | -9.529 | ***0.188 | -10.268 | ***0.718 |

| nonzero | -3.577 | ***0.083 | -2.861 | ***0.254 |

| Smaller server | 0.709 | ***0.032 | 0.629 | ***0.082 |

| Server size (outgoing) | 0.686 | ***0.013 | 0.655 | ***0.042 |

| Open registrations (incoming) | 0.168 | ***0.046 | -0.250 | 0.186 |

| Languages match | 0.044 | 0.065 | 0.589 | 0.392 |

To corroborate these findings, we also looked at accounts that moved from one server to another. We find that accounts are more likely to move from larger servers to smaller servers.

Recommender System

Based on the empirical findings, we create a recommendation system that can help people find Mastodon servers based on their shared interests. Figure 11 shows the system in practice. We use Okapi BM25 to construct a term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) model to associate the top tags with each server using counts of tag-account pairs from each server for the term frequency and the number of servers that use each tag for the inverse document frequency. We then L2 normalize the vectors for each tag and calculate the cosine similarity between the tag vectors for each server.

\[ tf = \frac{f_{t,s} \cdot (k_1 + 1)}{f_{t,s} + k_1 \cdot (1 - b + b \cdot \frac{|s|}{avgstl})} \]

where \(f_{t,s}\) is the number of accounts using the tag \(t\) on server \(d\), \(k_1\) and \(b\) are tuning parameters, and \(avgstl\) is the average sum of account-tag pairs. For the inverse document frequency, we use the following formula:

\[ idf = \log \frac{N - n + 0.5}{n + 0.5} \]

where \(N\) is the total number of servers and \(n\) is the number of servers where the tag appears as one of the top tags. We then apply L2 normalization:

\[ tf \cdot idf = \frac{tf \cdot idf}{\| tf \cdot idf \|_2} \]

We then used the normalized TF-IDF matrix to produce recommendations using SVD where the relationship between tags and servers can be presented as \(A = U \Sigma V^{T}\). We then use the similarity matrix to find the top servers which match the user’s selected tags. We can also suggest related tags to users based on the similarity between tags, \(U \Sigma\).

Model Evaluation

Evaluating recommender systems can be tricky because a measure of good performance must take into account various dimensions (Zangerle and Bauer 2022). A measure of accuracy must be paired with a question of “accuracy toward what?” Explainability requires a transparent way to show the user why a certain item was recommended.

It is often important to both start with an end goal in mind and to keep evaluation integrated throughout the entire process of creating a recommender systems, from conceptualization to optimization. There are several considerations to keep in mind such as the trade-off between optimizing suggestions and the risks of over-fitting. For example, a system designed to prioritize user interest may struggle with reduced diversity.

Recommender systems can be evaluated using three board categories of techniques: offline, online, and user studies. Offline evaluation uses pre-collected data and a measure to describe the performance of the system, assuming there is insufficient relevance to the difference in time between when the data was collected and the present moment. Online evaluation uses a deployed, live system, e.g. A/B testing. In this case, the user is often unaware of the experiment. In contrast, user studies involve subjects which are aware they are being studied.

To evaluate my system, I plan to use a mix of offline evaluation and user studies. For the offline evalulation, I plan to leverage known accounts which moved from one server to another. Based on their posting history (e.g. hashtags), can the recommendation system predict where they will move to? If the system ranks their destination server highly, this suggests it can do a good job recommending servers for the population of accounts which care enough about servers to move from one to another.

As my recommender system operates under the assumption that smaller, more topic-focused servers are better, it follows that a diverse set of niche results which only match a few tags are more helpful than a set of results which match a larger and more broad set of tags. The system therefore presents results sorted in a manner which encourages a higher diversity of results.

The inital results suggest the system does a decent job of matching moved accounts to their destination servers. On average, the system suggests the destination server as the 8th most likely option given an account’s post history.

Rules, Norms, and Content Moderation

While the Fediverse promises more autonomy in social media operations, most servers on the Fediverse have actually adopted similar rules, even directly copying them in many cases. Why, despite the opportunity to innovate, do Fediverse servers tend to adopt the same rules?

We consider this puzzle through the persepctive of institutional isomorphism. Through interviews with 17 server moderators and administrators combined with longitudinal records from thousands of servers, we find evidence of isomorphism between Fediverse servers and describe some of the mechanisms through which this occurs.

RQ1: How do rules originate and spread on the Fediverse?

RQ2: Why do Fediverse servers have similar rules?

Our study suggests that rules on the Fediverse perform an isometric role in addition to a practical role: as a signal to other servers and to people on the server. Rules encode not only what behaviors are permissible, but also community values.

Background

Institutional Isomorphism

Meyer and Rowan (1977) consider rules as myths which insitutions incorporate to bolster their own legitimatacy, sometimes at the expense of internal efficiency. Under this neo-institutionalist view, individual actions are constrained by societal expectations, which in turn lead to the development of formal and informal rules within insitutions.

P. J. DiMaggio and Powell (1983) consider the problem of why orginizations tend to look similar to each other and theorize that orginizations tend to adopt similar norms through a process of insitutional isomorphism, which has three types: normative, coersive, and mimetic. Normative isomorphic change is a byproduct of professionalization. Coersive isomporpohic change comes from pressures from other organizations. Mimetic isomorphism describes how orgainizations tend to imitate each other.

Rules and Content Moderation

Significant scholarship has investigated content moderation in the context of commercial, centralized social media platforms (e.g. Gillespie 2018; Roberts 2019). The function of content moderation in this context is shaped by economic factors: platforms often use contract labor and the people making case-by-case decisions are often divorced from the context of the communities they moderate (Gray and Suri 2019). However, a significant amount of the Web also relies on volunteer moderation: service work from unpaid people who are usually active members of their own communities. These volunteers might have different motivations for their actions.

While some commercial websites like Reddit allow volunteer moderators for sub-communities to create their own rules, moderators must also consider the site-wide rules (Fiesler et al. 2018). The Fediverse, by contrast, requires no base layer of rules for each community and account: there are no site-wide rules (Nicholson, Keegan, and Fiesler 2023).

Content Moderation on the Fediverse

Due to its technical design, the Fediverse faces unique content moderation challenges. Administrators may be responsible not only for posts on their own servers, but they may also have to deal with posts and conflicts from external servers. Like the servers themselves, the costs of content moderation is distributed among many servers. Server administrators may choose to block or silence accounts on other servers, but only the server operators have the powers to delete or directly sanction accounts.

Servers must also consider their relationship to other servers from which they may receive posts. Hassan et al. (2021) explored the use of server-to-server federation policies and suggested that some server-level blocks may have collatoral damage on some users. Colglazier, TeBlunthuis, and Shaw (2024) measured the effects of server-to-server de-federation events and found asymmetric effects on activity for affected accounts on the blocked servers.

Data

I collected metadata from daily snapshots from thousands of Fediverse servers between 2020 and 2025.

The period of this study came at a somewhat transitional point on Mastodon. Originally Mastodon rules were posted on the “about” page for the server. These rules often were long lists, often clearly copied from other servers. Mastodon v3.4 added an API field that allowed Mastodon administrators to add rules as server metadata.

flowchart TD

A[Raw Longitudinal Data] --> B{Filter Servers}

B --> E[Vectorize Rules with SBERT]

E --> F[Cluster Similar Rules]

Initial Findings

| Rule | Count |

|---|---|

| No racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, or casteism | 1925 |

| No incitement of violence or promotion of violent ideologies | 1629 |

| No harassment, dogpiling or doxxing of other users | 1581 |

| No illegal content. | 1273 |

| Sexually explicit or violent media must be marked as sensitive when posting | 1220 |

| Do not share intentionally false or misleading information | 1074 |

| Be nice. | 510 |

| No spam or advertising. | 410 |

| Don't be a dick. | 405 |

| Be excellent to each other. | 264 |

Interviews

We conducted interviews with 17 moderators and admins of Fediverse communities in 2022.

| ID | Software | Size | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| FV1 | Mastodon | [100–1K) | Regional |

| FV2 | Mastodon | [1K–10K) | Language |

| FV3 | Mastodon | [10–100) | Interest/Language |

| FV4 | Mastodon | [1K–10K) | Interest(?) |

| FV5 | Mastodon | [10-100) | Regional/Interst |

| FV6 | Pleroma | ? | |

| FV7 | Mastodon | [100–1K) | |

| FV8 | Mastodon | [100–1K) | |

| FV9 | Mastodon | [1K–10K) | |

| FV10 | Mastodon | [100–1K) | |

| FV11 | Mastodon | [100–1K) | |

| FV12 | Mastodon | [10–100) | |

| FV13 | Mastodon | [100–1K) | Interest |

| FV14 | Pleroma | ? | |

| FV15 | Pleroma | ? | Religion |

| FV16 | Misskey | ? | |

| FV17 | Mastodon | [100–1K) |

Identifying Communities

To identify communities of interest, we first considered the written rules on Mastodon and Pleroma servers. Starting with Mastodon Social, we used iterative sampling to discover new servers from the set of peer connections on previously known servers. We then downloaded the “/about/more” HTML data on Mastodon servers and the “/static/terms-of-service.html” HTML data on Pleroma servers as they appeared on September 25, 2021. I chose to go with a snapshot from September 25, 2021 as this was before the rules API feature got added to Mastodon and so we get the richest text content. Using these HTML data, we filtered to only servers which had texts in English, had over 100 tokens of text on these pages (after removing stop words, articles, and non-letters). From this matrix, we calculate the pairwise similarity between all M documents by counting the number of n-grams they share in common using the following formula:

\[ \frac{\text{count}(X_1 \cap X_2)}{\min(\text{count}(X_1), \text{count}(X_2))} \]

I then created clusters using the HDBSCAN algorithm to construct clusters of similar rules. We recruited participants with the goal of representing servers in each main cluster.

Qualitative Analysis Methods

I plan to use directed qualitative content analysis, starting under the framework of institutional isomorphism. Several practices that lead to rule creation suggest strong institutional isomorphism amoung Fediverse servers (Figure 14).

Rules Memos

Applying local rules to external posts

Some servers attempt to apply their own local rules to posts on other servers. This may create significant difficulties when federating with other servers.

For example, FV15 is a religious community whose members hold strong beliefs about appropriate content. For this community, part of the service they provide to their members is not only ensuring that the posts on the local timeline follow the community values, but also that all posts in their known network are compliant. A further motivation toward their approach comes from how the Fediverse works: they do not want to host copies of posts which violate their policies.

Yeah. Honestly, most moderation is manageable if your users stick to the same rules that everybody else that the server has. If they don’t, that’s when you have most of your issues with moderation.

Proactive and reactive moderation

There are two common approaches toward moderation. One tries to be reactive, only taking action after harm has occured; the other tries to be proactive to reduce the chance of harm in the future.

The proactive approach can be represented in the #FediBlock hashtag, which Mastodon moderators use to share and discuss harmful users and servers with each other.

Rules as signposts

Some Fediverse servers use their rules and community metadata as signals to other communities.

When dealing with external servers, staff have limited information to get a picture of how the server works. The rules can thus be a strong signal of a server’s values. If a post is clearly in violation of its host server’s rules, this can signal that the server staff simply have yet to get around to removing it rather than the alternative narrative that it represents typical content found on the server.

Rules to solicit reports

On Mastodon, the rules API is tied to the reporting feature. People can report posts that violate the rules to the staff on their local server and optionally choose to forward that report on to the post’s originating server.

If server staff deal with posts commonly on large servers, it may make sense to adopt similar rules so they can forward those reports on to the larger server’s staff.

Network integrity

Some staff value upholding the network integrity of the Fediverse. They believe that servers blocking each other breaks the user experience. Instead, they prefer to take actions against people, not entire communities.

Plan of Study

I’m interested in using these data to answer some questions about how these rules developed. Are rules more likely to change over time on larger servers when new issues arise such as AI-generated content? Are certain servers more likely to change and adopt those rules than others? Do servers tend to adopt more rules if they talk more with servers that have those types of rules? These are angles that the quantitative data can help answer.

On the qualitative side of things, I have data collected from 17 interviews with Fediverse administrators and moderators. Those interviews can tell us not only what is happening, but also why this is happening. They have the potential to generate a lot of insights into how server administrators think about the rules and the relationship between rules and Fediverse communities. In preparation for the qualitative data anlysis, I read through Sarah J. Tracy’s Qualitative Research Methods book.

Status and Timeline

My current goal is to complete my defense by the end of the current academic year.2 I believe this should allow for a realistic timeline barring any unexpected circumstances.3

Thankfully, I am not starting from scratch on any of the three studies:

Study 1 (de-federation) has been published as Colglazier, TeBlunthuis, and Shaw (2024) at ICWSM

Study 2 (newcomers) has been presented as Colglazier (2024) at a workshop and at \(IC_{2}S_{2}\)

Study 3 (rules) has completed the data collection phase and some of the analysis has been completed

Significant work is still needed on analysis of the qualitative interviews for Study 1, the rules data for Study 1, and refining and evaluating the recommender system in Study 2.

References

Footnotes

While email is a decentralized system by design, in practice it has become more centralized over time. For instance, Google’s Gmail service is a dominant provider of email services. Smaller email providers may struggle to get through Gmail’s spam filters, increasing the incentive to simply use Gmail. This means that in practice, Google still has a great amount of data even on people who opt not to use Google’s services (Hill 2014).↩︎

And certainly before my wedding in September!↩︎

Illnesses, injuries, etc.↩︎